|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

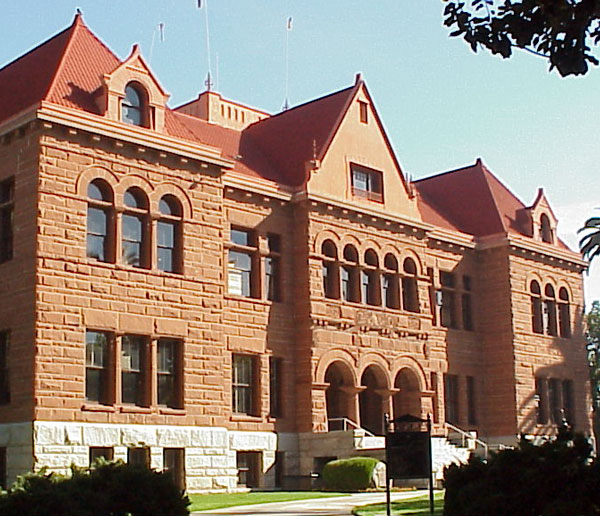

Actions in Orange County Superior Court -- Tips, Information and Urban Legends

When I received the summons and complaint, there was a form attached that said my trial date is in about four months. Can I just wait until then, show up and tell my side of the story? That's not the trial date. For some reason, when some people receive a summons and complaint, their eyes glaze over and they can't or won't read the papers to see what they are supposed to do. The summons clearly states that you must file and serve an answer within 30 days (it's only FIVE days for some complaints, so read carefully). Inexplicably, that part never gets read. Instead, the defendant turns to what is called the notice of case management conference, where a date is stamped in big black ink. The document explains that is the date of the Case Management Conference, and also explains that the defendant has only 30 (or five) days to answer. For whatever reason, many people think that is a hearing date, and that they can just show up on that date. The Case Management Conference is a procedural hearing, designed only to make certain the case is moving forward, and sometimes to set a trial date. Neither party is permitted to talk to the court about the merits of the case. In fact, often the judge never takes the bench, and the process is handled by the clerk. If you do not file an answer to the complaint or respond in some other proper way, and wait until the Case Management Conference to do anything, a judgment will have already been taken against you and plaintiff will be in the process of seizing all your worldly belongings. In fact, isn't that your car being towed away right now? I found a summons and complaint stuck under the windshield wiper of my car (or nailed to my door, or left at my office). I know that's not proper service, so do I need to file an answer? Playing the, "I wasn't properly served" game is fraught with peril. If you receive a complaint, even if it was nailed to your door, never, ever ignore it. As you'll see, it usually doesn't make sense to fight over service. There are a number of urban legends about service. Many people think it's like a game of tag, and that service is ineffective unless the process server gets the defendant to take the documents in his or her hand. That's a dangerous myth. It's not even true that the process server has to personally serve you. By law, the process server is supposed to try to personally serve you. If he does find you, he is supposed to tell you the nature of the documents, so that you won't think it's someone trying to hand you religious literature. So, the process server will walk up to you and say, "Mr. Rogers, this is a summons and complaint." If you take it from him, great, if not, he can drop it at your feet. He could even approach you in your car, make the statement, and stick it under your windshield wiper. So, yes, sticking it under your windshield wiper can be effective service. If he makes three attempts to serve you, but can't find you at home or work, he can substitute serve you by giving it to someone at your home who is over the age of 17. He must then mail you a copy as well, to make sure you get it even if your no-good adult son that answered the door never gives it to you. That process server will now prepare a proof of service, attesting to the fact that you were served. Thirty days later (40 days for substituted service), the opposing party will take a default against you, and then seek an unopposed judgment. In one case, a client came to us who had ignored a complaint that involved $35,000. With no opposition, the plaintiff was able to convince the court to award $1.2 million. We were able to get it reversed, but not without much effort. Indeed, it can sometimes be a brilliant strategy to answer before you are ever served. Some lawyers file a complaint to preserve the statute of limitations but then hold it for three or four months because they want to accomplish something before they serve you. Perhaps there is a witness crucial to the case they are trying to locate, or the corporation that is suing you is no longer in good standing and the attorney needs to get it revived. If you answer before the attorney is ready to proceed, it can really put a kink in his or her litigation strategy. Of course, you would only do this if it made sense given the specific circumstances, otherwise you might expose yourself to unnecessary litigation. If you are improperly served, don't ignore it. Go to court and fight the service if it makes you feel better. You'll still be served, probably in the hallway as you leave. Judges in the Orange County Superior Court are more interested in whether there was constructive notice as opposed to worrying about the technical requirements of service. You or your attorney will look foolish when you stand in front of the judge and proclaim, "your honor, I was never served with the complaint that . . . I'm . . . um . . . holding . . . here in my hand." It's usually better and cheaper to just answer the complaint. Many amateur attorneys think that good advocacy requires them to fight everything. A good attorney knows how to pick the battles. I just got served with a complaint that the judge will be able to tell just from reading it that the case is without merit. I mean, for God's sake, the plaintiff says I'm from Mars and that I'm mentally attacking him in his dreams. Do I really need to respond to the complaint? Yes, you must respond to the complaint. The question is reasonable, but based on a false assumption. It is essential that you understand that NO ONE AT COURT WILL EVER READ THE COMPLAINT. Let me explain the process. A lawsuit is commenced by the filing of a complaint. When the complaint is filed, the clerk stamps a date on it, returns a stamped copy to the plaintiff, and then puts the complaint in the file, never to be seen again. The defendant reads the complaint to file an answer, and the answer follows the same process. No one at court reads the complaint or the answer. Even if the case goes all the way to trial, no one at the court will ever read the complaint or answer, UNLESS those documents are somehow put in dispute by the parties. Let's use our Man from Mars complaint to show just how far this goes. You are sued by someone for infliction of emotional distress because, according to the complaint, you are a Martian and you are attacking him in his dreams. You want to get the judge to take a look at the complaint, so you file what is called a "demurrer," which states that the complaint fails to state a cause of action. The judge will then look at the complaint, because you forced him or her to do so. But even then, the judge MUST assume that all the allegations in the complaint are true. So, the complaint says you are a Martian, and you have mental powers you are using to attack him. Taking those facts as true, then the plaintiff has properly stated a cause of action for infliction of emotional distress, and you will be ordered to answer the complaint. Why is such an absurd result permitted? The reason is that cases must be decided by the EVIDENCE. Again, let's use our crazy facts to illustrate the point. This time, we'll make you the plaintiff. You were happily living your life in your home, but a Martian really did move in next door and he really is attacking you in your dreams. Do you want the judge to have the power to throw out a complaint based only on his own beliefs or understanding of the facts? How will we ever stop the evil, mind-controlling Martians if every judge throws out any complaint involving extraterrestrials? OK, the Martian example is extreme, and the truth is you probably could get the judge to take judicial notice that no Martians have ever visited Earth and dispose of the case by way of demurrer. But what about cases that are not so extreme? What if you are suing because you tripped on a crack in a sidewalk that was not properly maintained? Should the judge be able to throw out your complaint, because he doesn't remember seeing a crack the last time he walked on that sidewalk, or because he believes that no one is clumsy enough to trip on a crack? Don't you want the opportunity to present your evidence before the judge decides the merits of your case? Bottom line. When you are being sued for what you think is a frivolous reason, it gets very frustrating that you must go through the process for a period of time before you can force the judge to examine the facts and evidence by, say, a motion for summary judgment. But that is the price you pay for the day that you become the plaintiff and don't want your case thrown out on the whim of a judge who has never seen your evidence. No one is better than Morris & Stone at disposing of frivolous cases, but even we must use the process. I need to file a complaint or answer in Orange County Superior Court, but can't afford the filing fee. Can I get it waived? Yes, and the Orange County Superior Court is fairly generous in granting such requests, if your financial circumstances so warrant. Here is the packet you need to complete. The packet is daunting, but if you have more time than money it's an option. I am owed money by the defendant, but I know he doesn't have any assets. Is there any point in suing him? One rule that is specific to Orange County Superior Court is local rule 317 (formerly Rule 450). This rule requires the parties to meet and confer at least ten day prior to trial in order to reach agreement on certain items (if possible) such as he statement of the case and the stipulated facts. Rule 317 also requires the parties to exchange trial exhibits prior to trial. Some judges are very strict on this rule, and we have been successful in excluding all of the opposition's trial exhibits based on their failure to exchange them prior to trial. I was served with a summons and complaint, and the summons says that I need to file an answer within 30 days. What does an answer look like? Is it something I can just pick up at the Orange County Superior Court? You can get a form answer at the Orange County Superior Court, fill it out and file it, but that's usually not a good idea. Here's how pleading works. The plaintiff is supposed to serve and file a complaint that sets forth sufficient facts so that you know what you are being sued for. The complaint sets the parameters for the action. If the complaint says you owe plaintiff money because you borrowed money and didn't pay it back, he can't spring on you at trial that you also stole money from him. The plaintiff is bound by the complaint. And so it is with the answer. You must set forth the defenses you will rely on in defending against the complaint. If it's not in your answer, you may be barred from using that defense at trial. Wouldn't it be ashamed if you ended up paying money you did not owe, just because you left some magic words out of your answer? I know that I am required to answer the complaint. Can I just send a letter to the judge explaining what happened? An answer is a specific type of document, and a letter does not qualify. A judge is not permitted to read any letter that you send, because that would be what is called an ex parte communication. A judge is never supposed to talk to one side without the other side being present. A possible exception is Small Claims Court. Since that is designed to be layperson friendly, a judge will read the letter to see if you are asking for an extension. What do I say in the answer? Is that where I tell my side of the story? Can I just use the "check-the-box" form I found on line? Here is the way it is supposed to work. The plaintiff files a complaint which is supposed to contain enough facts so that the defendant can properly know of what he or she is being accused. If a complaint just said, "defendant injured me," that would not be sufficient. The defendant would not know whether he is being accused of assaulting the plaintiff, or perhaps was involved in an auto accident with the plaintiff. The complaint needs more facts. Similarly, an answer is supposed to contain sufficient facts so that the plaintiff will know the basis upon which the defendant is denying the allegations of the complaint. But for some reason no one does it that way. Most defendants will simply file what is called a "general denial," claiming that all the allegations of the complaint are false. This is a legal fiction, because even the defendant will admit that some of the allegations are true, such as the county where he resides. If a plaintiff really wants to force the defendant to file a more meaningful answer, he can file a verified complaint. With a verified complaint, the plaintiff states under penalty of perjury that all of the allegations are true. The defendant, under most circumstances, must then file a verified answer, either admitting or denying each of the allegations in the complaint. Generally it is considered a bad idea to file a verified complaint unless a particular cause of action requires it, because as you conduct discovery in a case, your understanding of the facts might change. As to the check-the-box answer you can get from the court, utilizing that form can be a really bad idea. The answer must also contain any "affirmative defenses" upon which the defendant intends to rely. A general denial puts in dispute any allegations that are specifically refuted by that denial. In other words, if plaintiff alleges you owe him $100,000, your general denial will be sufficient to allege that you don't owe him $100,000 (although some attorneys will argue that does not deny that you owe him $99,999). But any defense that goes beyond a direct denial requires an affirmative defense. This is sometimes called the "yes, but" test. In other words, if in response to an allegation in the complaint, your response is, "yes, that allegation is true, but . . .," then a general denial does not properly refute that allegation. There are many affirmative defenses that must be set forth in the answer or they are waived (although the court might give you permission to amend the answer to add a defense). In other words, you could go to trial and lose because you can't rely on a defense that would have defeated the claim. One of the best examples of this is the statute of limitations. Take an oral contract. Under the statute of limitations, an action on an oral contract must be brought within two years of the breach. Defendant sues you three years after the breach, and you file an answer with no affirmative defense for the statute of limitations. If you had alleged that affirmative defense, you could have won the case by simply proving that the breach occurred more than two years before the complaint was filed. Without that defense, the judge will not permit you to rely on that defense (because you did not put plaintiff on notice that was your intention), and you will need to find some other reason that you are not responsible for the debt. I want to include a claim for punitive damages in my complaint. How much should I ask for? Many amateur attorneys used to play the game of asking for $10 billion as punitive damages, thinking the amount was so shocking that it would somehow intimidate the other side. Sometimes it would even generate press coverage. After all, someone being sued for $10 billion in Orange County Superior Court must have done something really bad, right? In response, the California Legislature passed a law making it improper to allege an amount of punitive damages. You must still ask for punitive damages in your complaint if there is a basis for recovery, but you may not set forth an amount. As satisfying as you might find it to ask for $100 trillion in punitive damages to show how outrageous the conduct of the defendant, all that will happen is the court will strike the allegation and possibly sanction you. By the way, you cannot recover punitive damages in a breach of contract action. Should I sue everyone that might be responsible for my damages? Can't I just dismiss if I'm wrong? Another common mistake made by people representing themselves, as well as amateur attorneys, is to sue everyone they can think of, and throw in every conceivable cause of action. The thought is that even if someone is named as a defendant that shouldn't have been, the action can always be dismissed as to that defendant. Unscrupulous attorneys will try to settle with the improperly named defendants, offering to dismiss the action for, say, five or ten thousand dollars. This is common in construction defect cases, where the plaintiff's attorney will name every subcontractor. Even if the claimed defect is soil subsidence, they'll name the guy that installed the air conditioning. Naming too many defendants and "over-pleading" (listing too many claims) are both bad strategies if the attorney on the other side knows what he or she is doing. For example, let's assume my client is a construction corporation that bought some building materials from you, but due to a downturn in the housing market is unable to pay you when due. You go to an attorney who properly sues the corporation, but then thinking it will apply a little more pressure, he also sues my client as in individual, even though it was the corporation that bought the materials. For even more pressure, the attorney also sues for fraud, not just breach of contract. By suing for fraud, you could recover punitive damages, so that make the action much scarier for my client, or so your attorney thinks.

Even though you won on one cause of action, my clients prevailed on three. That makes them the prevailing parties. They will recover all attorney fees and costs, assuming there was a basis for attorney fees, and that total may well exceed the amount you recover for breach of contract. If there is no basis to recover attorney fees directly, no problem, we then just sue for malicious prosecution and recover them that way. All because your attorney named too many defendants and causes of action. It's a balancing act when you draft a complaint, because you do want to allege all appropriate causes of action in case one gets thrown out, against all the appropriate defendants, but as you can see it can be perilous to over-plead. Be sure to consult a competent attorney. What is the difference between mediation and arbitration? Mediation - A process in which a neutral third person meets with the parties to a dispute in order to assist them in formulating a voluntary solution to the dispute. Arbitration - Using a neutral third person to resolve a dispute instead of going to court. The parties can agree whether the arbitration will be binding or non-binding. As you see from the definition of mediation, the mediator assists the parties in formulating a voluntary solution to the dispute. We sometimes see agreements drafted by attorneys that call for "binding mediation." There is no such thing, since that implies that the parties will be bound by the decision of the mediator. The mediator doesn't make a decision; he only tries to get the parties to agree to a resolution. You could, theoretically, agree that a third party will have the absolute right to decide how the parties will resolve the case, but that is not mediation. Mediation is sometimes required by an agreement, but that just means that the parties must get together and try to work out their differences. In many standard real estate agreements, the parties are required to mediate the dispute before going to court. Sadly, we have seen a number of cases where the attorney ran to court and filed a complaint without reviewing the agreement closely enough to see the mediation requirement. By the terms of the agreement, that waives the recovery of all attorney fees. Even if a party is certain that mediation will be unsuccessful, it is far better to spend an hour or two going through the process to preserve the right to recover attorney fees. Arbitration is not mediation, although sometimes even arbitrators lose sight of this fact. An arbitration is an informal trial, and should follow the same rules of evidence. Many courts will order you to non-binding arbitration, hoping that will resolve the dispute. But what is to keep the loser from simply rejecting the arbitrator's decision if the arbitration is non-binding? Nothing, but who won and lost is not always so clear. Say, for example, an employee is suing for wrongful termination, and thinks he is entitled to $400,000. He goes to the arbitration and wins, but the arbitrator finds that he failed to mitigate his loss of future wages, and awards only $75,000. The defendant employer might reject the award to avoid paying $75,000, but it might decide that is better than going to court and running the risk that the jury will award the full amount. The plaintiff employee might reject because he got far less than what he asked for, but he could also be educated by the process and realize that his case wasn't the slam-dunk he thought it was. I seldom reject the option to mediate a case. It provides an independent view of the case by an impartial third party. You either reach an agreement or you don't, and there is no downside. I've seen good mediators settle cases I never thought would settle. On the other hand, I seldom agree to non-binding arbitration unless the court orders me to go. If the case requires expert witnesses, you must pay them twice -- once for the arbitration and again at trial. Similarly, you must inconvenience your witnesses twice if the matter doesn't settle (although you can under certain circumstances use declarations or deposition transcripts in lieu of live testimony). The other side lied during the trial, and as a result the judge entered a judgment against me. Can I sue for perjury or defamation because of the lies? You or your attorney should have assumed that the other side would lie and prepared your case in anticipation of that fact. And if you testified but the judge chose to believe the liar on the other side, what does that say about your perceived credibility? For whatever reason, the judge did not believe you, so why would a new trial, where you again claim that the other side is lying, come out any differently? Anything said in court is absolutely privileged, meaning that you can't sue. Your remedy for a bad judgment is to appeal or bring a motion for a new trial. If parties could start new actions to address perceived grievances from other actions, the process would never end. If you can convince the District Attorney that a witness lied on the stand, he or she can be criminally prosecuted for perjury. In the more than 20 years I've been practicing, I've seen that happen . . . never. But that doesn't mean that the system doesn't work. It's called an adversarial system for a reason. And if your case is presented properly, truth will prevail over lies. I am owed $8,000 (or $9,000 or $10,000). I've talked to a few attorneys and they all tell me it would cost more to sue using an attorney than I could recover. Am I out of luck? Don't I get back the attorney fees if I win? First the attorney fees. Generally you DON'T get back your attorney fees unless there is a contract that provides for attorney fees, or some special statute. If you are owed money pursuant to a contract or promissory note, look at the document to see if it provides that you can recover your attorney fees. By the way, attorney fees are always reciprocal, even if the contract says something different. For example, a promissory note may say that only the lender is entitled to recover attorney fees, but if the lender sues and you win, you would get your fees. As Abe Lincoln said, "an attorney's time is his stock in trade." You may think that an attorney's time is free, but every hour the attorney spends on your case is an hour he or she is not being paid on another case. I sometimes get calls from prospective clients that want me to handle their $400 collection case. When I ask how they were anticipating paying an attorney to handle a $400 case, they tell me they thought I would work on a contingency basis, taking a percentage of the $400. But some assume I could do the work, and then recover my usual hourly fees. The problem with that approach is that even when the contract provides for attorney fees, it is always "reasonable" attorney fees. When a judge is determining what is reasonable, he or she will always consider the result that was achieved. If an attorney runs up a bill of, say, $3,500 to collect $400, the judge may find that to be unreasonable and only award $1,000 in fees. And so it is with your $8,000 claim. No experienced attorney will take a case in the hope of recovering his standard hourly fee, when he can earn that fee through paying clients. If you are willing to take that risk by paying the fees up front on the hope that you will recover them from the defendant, then you can probably find an attorney. But even without an attorney, you can still pursue your claim. You can now sue for up to $7,500 in Small Claims Court. If your claim is for more than $7,500, you just waive the rest. So, pursuing an $8,000 claim in Small Claims Court means you are giving up $500 that you are owed, but that is far cheaper than what it would cost you to hire an attorney. A business claims I owe them $450 and has dinged my credit, but I can prove I don't owe that money. I've called and written a million times, but they just ignore me. Can I sue? You can sue for what is called declaratory relief, but that can only be done in Superior Court (not small claims), and it will cost you thousands of dollars if you hire an attorney. If you follow certain procedures and the business fails to comply with the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, you can sue, but again that will cost you thousands of dollars. These traditional approaches just are not very practical because of the amount involved. But here is my patented Small Claims Court procedure that can solve the problem for about $40, assuming it is a local business. Pay the amount under protest, and then sue to get it back. Small Claims Court is not a court of equity, it can only award damages. This means that you cannot go to Small Claims Court to declare that you do not owe the money. But you can accomplish the same thing by paying the money under protest and then suing to get it back. The judge will then have to make the determination that you never owed the money. Be forewarned, however. This approach is too sophisticated for some judges. With these judges, the conversation will go something like this: "Your Honor, I'm seeking reimbursement of the $450 I paid to defendant under protest." "But didn't you owe the money to defendant?" "No, your Honor, that's the point. I never owed the money to the defendant, I only paid it under protest so that I could sue in Small Claims Court to get it back. Otherwise, there is no simple mechanism to have a court determine that the amount is not owed." "Why would you pay the money if you didn't owe the money?" "Because the defendant reported it as a unpaid debt to all the credit reporting agencies. I don't have the thousands of dollars it would take to sue in Superior Court to have the matter decided and clear up my credit reports, so by paying the money under protest and then suing to get it back, I will now have a judgment showing that I do not owe the defendant any money. I can then provide that judgment to the credit reporting agencies in order to remove this false information. Or, if I challenge the information on my credit reports and defendant continues to report that the information is accurate, even after it was determined in Small Claims Court that I never owed the money, then I will have an outstanding case against the debtor for violation of the Fair Debt Collections Practices Act." "So you paid the money to defendant, just so you could turn around and sue to get it back? That's the craziest thing I ever heard. Judgment for defendant, and don't ever waste my time like that again." All you can do is hope you don't get one of those judges. How much can I sue for in each court? In Orange County Superior Court, you have four basic ranges that dictate where you will file a civil action. Small Claims Court, a part of the Superior Court, handles claims up to $7,500. You can also sue in what is called limited jurisdiction Superior Court for any amount from $0 to $25,000. These were called Municipal Courts until a few years ago, when they were consolidated into the Superior Courts. Claims for $10,000 or less are handled a little differently, but by the same courts. Generally if the claim is less than $7,500 you would want to take advantage of the faster and cheaper Small Claims Court, but there are times when you are not permitted to file your action there, such as when you have filed more the the number of claims you are permitted in a year, or when you want to be represented by an attorney (you cannot be represented in Small Claims Court). Claims of more than $25,000 are filed in Orange County Superior Court as "unlimited." Perfectly clear? Litigation is never easy. Web site of the Orange County Superior Court. Orange County Superior Court Forms. Common Time Frames in Unlimited Superior Court

Service, Return of Summons Serve all named defendants, and file proof of service with the court, within 60 days from the date the complaint is filed. (Local Rule 2.1.5.) Answer File an answer within 30 days after personal service. (CCP §412.20(a)(3).) Cross Complaint Generally must be filed at the same time the answer is filed, i.e., within 30 days after service by personal service. (CCP §428.50(a).) Motions Generally must be served and filed at least 16 court days before hearing, with an additional 5 days’ notice given if served by mail within California, an additional 10 days’ notice if served outside of California, an additional 20 days’ notice if served outside the United States, or an additional 2 calendar days’ notice if served by facsimile or express mail. (CCP §1005(b).) Papers opposing a motion or replying to an opposition are to be served so that delivery is ensured to be made to the other parties no later than the close of the next business day. (CCP §1005(c).) This time frame includes motions for summary judgment/adjudication as well. Proof of service of the moving papers must be filed no later than 5 court days before the hearing. (CRC 3.1300(c).) Demurrer, Motion to Strike, Judgment on the Pleadings Within 30 days after service, unless extended by stipulation or court order. (CCP §430.40(a); 435(b).) Demurrer to the answer, within 10 days after service of the answer. (CCP §430.40(b).) Statutory motion for judgment on the pleadings cannot be made after entry of a pretrial conference order or 30 days before the initial trial date, whichever is later. (CCP §438(e).) Summary Judgment/Adjudication Motions Must be served and filed at least 75 days before hearing, extended by 5 days if served in California, 10 days if served outside California, and 20 days if served outside the United States. (CCP §437c(a).) Opposing papers must be served and filed not less than 14 days before the hearing. (CCP §437c(b)(3).) Reply papers must be served and filed not less than 5 days preceding the hearing. (CCP §437c(b)(4).) Discovery Motions Motions to compel where no response at all to interrogatories or document requests have been served may be made at any time. (CCP §§2030(k), 2031(l).) Motions to compel further responses to interrogatories or document requests must be made within 45 days after service of the response, extended 5 days if served by mail in California; otherwise, the propounding/demanding party waives any right to compel a further response. (CCP §§2030.00 (2)(c).) A motion to compel answers to deposition questions must be made no later than 60 days after completion of the record of the deposition. (CCP §2025.480 (b).) Miscellaneous Motions Motions for sanctions under CCP §128.7 cannot be made until 51 days after service of the motion on the party said to be in violation. (CCP §128.7.) Motions for dismissal under the two-year discretionary statute must be made at least 45 days before the hearing. Opposition is due within 15 days after service of the notice of motion. Response to the opposition is due within 15 days after service of the opposition. A reply to the response is due within 5 days after service of the response. (CRC 3.1342.) Motions for reconsideration must be made within 10 days after service of written notice of entry of the order to be reconsidered. (CCP §1008(a).) DefaultsWhat Judicial Council form must the Plaintiff file to obtain DEFAULT against a defendant who has failed to timely answer the complaint? CIV - 100 Request for Entry of Default What Judicial Council form must the Plaintiff file to obtain DEFAULT JUDGMENT against a defendant whose default has been entered? The same form -- CIV - 100 -- is used, but the Applicant must be sure to check the box in the caption indicating whether a Clerk’s Judgment or Court Judgment is being sought. Failure to check the appropriate box is a very common error. In addition, the Applicant must either check the box at ¶ 1 (d) or at ¶ 1 (e) indicating whether a Clerk’s Judgment or Court Judgment is being sought. (See also CRC 3.1800.) Counsel should also file a Proposed Judgment. (CRC 3.1800 (a)(6).) It may be most convenient to use Judicial Council form JUD-100. However, if a case is particularly complex, involving multiple defendants and significant amounts of overlapping and non-overlapping damages, it may be preferable for counsel to draft a Proposed Judgment tailored to that specific case, which explains precisely how damages are to be awarded and whether each of the multiple defendants is solely liable, or jointly and severally liable for each particular element of the damages award. Are there any relevant statutes the Plaintiff should review before seeking entry of default and default judgment? Yes. CRC 3.1800 sets forth a list of specific requirements, which the Applicant must satisfy when seeking entry of default judgment, on declarations. CCP 585. CCP 586. Appendix A to the Local Rules. And Civil Code sections 1717 and 1717.5. Must the Plaintiff include interest calculations? Yes. Please submit a declaration showing in specific detail how the interest was calculated, so that the court may verify the accuracy of the calculation. (CRC 3.1800 (a)(3), 3.1802.) Please show the applicable interest rate per annum, the starting and ending dates for which interest was calculated, and the total number of days for which interest was calculated, the per diem rate of interest, and the total interest. Failure to include such calculations is a common oversight. Must the Plaintiff complete the Declaration of Mailing at ¶ 6 of the form CIV - 100 Request for Entry of Default? Yes, this Declaration is required by CCP 587 when seeking entry of DEFAULT. Absent filing of this declaration, the clerk may not enter defendant’s default. The Declarant should remember to sign the declaration, enter the date, and check the appropriate box under paragraph 6. If applicable Declarant should provide the last known addresses for each of the defaulted defendants under paragraph 6 (b). Must the Plaintiff complete the information at ¶ 2, ¶ 7, and ¶ 8 of the Request for COURT JUDGMENT form, relating to damages, costs, and fees; the memorandum of costs; and the declaration of military status? Yes, this information must be completed when seeking DEFAULT JUDGMENT. (CRC 3.1800 (a)(4), (a)(5).) In what types of actions may the Plaintiff obtain a DEFAULT JUDGMENT solely on DECLARATIONS, without any hearing? Under CCP 585 (a), Plaintiff may seek DEFAULT JUDGMENT on DECLARATIONS in an action arising upon contract or judgment for the recovery of money damages, IF the defendant(s) have NOT been served by publication. In what types of default actions must the Plaintiff set a LIVE HEARING to PRESENT EVIDENCE OF DAMAGES? In non-contract actions where the defendant(s) have NOT been served by publication, the court must hear evidence of Plaintiff’s damages. (CCP 585 (b).) In all actions where the service of the summons was by publication. (CCP 585 (c).) In quiet title actions and in cases where the defendant has been served by publication and is a non-California resident. (CCP 764.010; Winter v. Rice (1986) 176 Cal.App.3d 679, 683; CCP 585 (c). Must the Plaintiff serve a Statement of Damages? If the action is one for personal injury or wrongful death, a Statement of Damages must be PERSONALLY SERVED on the defendant BEFORE entry of default. (CCP 425.11 (c), (d)(1).) Plaintiff should file the proof of service with the court as soon as possible. Must the Plaintiff serve a Statement of Punitive Damages? If the action seeks punitive damages under Civil Code section 3294, a Statement of Punitive Damages must be PERSONALLY SERVED on the defendant BEFORE entry of default. (CCP 425.115 (f), (g)(1).) Plaintiff should file the proof of service with the court as soon as possible. Note that the Plaintiff may serve a single document, which combines both the Statement of Damages and the Statement of Punitive Damages. (CCP 425.11 (e); CCP 425.115 (e).) In an action brought against multiple defendants, as a general rule, may the Plaintiff obtain default judgment against a single defendant, where there are co-defendants whose defaults have not been entered? No. As a general rule, if a co-defendant has answered and has raised defenses, which may exonerate the defaulted defendant, then default judgment is improper and may not be taken against the defaulted defendant. (Adams Manufacturing & Engineering Co. v. Coast Centerless Grinding Co. (1960) 184 Cal.App.2d 649, 655; Mirabile v. Smith (1953) 119 Cal.App.2d 685, 689.) May the Plaintiff obtain judgment on claims that are not well-pleaded? No. As a general rule, a defendant who defaults only admits facts well-pleaded in the complaint. If the complaint fails to state a cause of action, a default judgment is erroneous and may be set aside on appeal. (Molen v. Friedman (1998) 64 Cal.App.4th 1149, 1153-1154.) May the Plaintiff obtain a type of relief or an amount of money damages not pleaded in the complaint? No. As a general rule, the court MAY NOT grant a TYPE of relief that was NOT pleaded in the complaint. (Marriage of Lippel (1990) 51 Cal.3d 1160, 1166; CCP 580.) Similarly, as a general rule, in actions for money damages, the court MAY NOT grant damages in an AMOUNT, which was not pleaded in the complaint. (Becker v. S.P.V. Construction Co. (1980) 27 Cal.3d 489, 493.) DemurrersWhat is a demurrer? A demurrer is a pleading that challenges the sufficiency of the complaint, cross-complaint or answer. It raises issues of law, not fact. Generally, a demurrer to a complaint or cross-complaint asserts that, even if all the facts alleged in the complaint or cross-complaint are true, they do not state a claim the law recognizes; that is, they do not state a claim for which the court can grant relief. A demurrer may also assert other deficiencies, for example, that the court does not have jurisdiction of the claim asserted in the complaint or cross-complaint, that the claim is already before the court in another case, that the proper parties have not been included in the case, or that the responding party cannot understand what is being alleged. (Code Civ. Proc. § 430.10.) Generally, a demurrer to an answer asserts that, even if all the facts alleged in the answer are true, they do not constitute a defense to the claims alleged in the complaint. It may also assert that the answer cannot be understood. (Code Civ. Proc. § 430.20.) When must demurrers be filed? The demurrer to a complaint or cross-complaint must be filed and served within 30 days after service of the complaint or cross-complaint. (Code Civ. Proc. §§ 430.40(a), 432.10.) In unlawful detainer actions, a demurrer to the complaint must be filed and served within 5 days after service of the complaint. (Code Civ. Proc. §§ 1167, 1170.) A demurrer to an answer must be filed within 10 days after service of the answer. (Code Civ. Proc. §§ 430.40(b).) How and when must demurrer papers be filed and served? The demurrer papers must be filed and served at least 16 days before the hearing, plus additional days if the papers are served by mail, overnight delivery or fax. (Code Civ. Proc. § 1005(b); Cal. Rules of Court, rule 3.1320(c).) Demurrers must be set for hearing not more than 35 days after the filing of the demurrer, or on the first date available to the court thereafter. (Cal. Rules of Court, rule 3.1320(d).) What papers must be filed?

(Cal. Rules of Court, rule 3.1112(a); Code Civ. Proc. § 430.30(a); Evid. Code §§ 451, 452, 453.) When must a demurrer be taken off calendar? The moving party must immediately notify the court if the demurrer will not be heard on the scheduled date. (Cal. Rules of Court, rule 3.1304(b).) Plaintiff may file a first amended complaint while a demurrer to the original complaint is pending; the first amended complaint supersedes the original and renders the demurrer moot. (Code Civ. Proc. § 472.) If a first amended complaint is filed, the demurring party must notify the court and take the demurrer off calendar. (Note: Filing a second or subsequent amended complaint without leave of court is not permitted and does not require taking off calendar the demurrer to the first or subsequent amended complaint.) DiscoveryThe following consists of very general information concerning Discovery. It is not all-inclusive and is meant to be a guide only. Litigants representing themselves are still encouraged to seek the advice of counsel. What is discovery? Discovery is the term used for obtaining information that will help a litigant prosecute or defend the action from other parties to the lawsuit and in some instances, from persons and entities that are not parties to the lawsuit. How do I obtain this information? By propounding (picking and choosing from among pre-formatted questions or forming your own) and serving form interrogatories, specially prepared interrogatories, requests for admissions, inspection demands and notice of depositions. Various types of form interrogatories, requests for admissions, inspection demands and notices of depositions can be obtained from the Book of Judicial Council Forms or books of discovery forms available from legal publishing companies. The rules for discovery and for each different type of discovery are set forth in the Code of Civil Procedure § 2016 et seq. Time limits for discovery in general Generally, a case must be pending before discovery can begin. See CCP § 2017. Plaintiffs must obtain a court order based upon a showing of "good cause" to begin discovery during the first 10 days (20 days for a deposition) after a defendant is served with the summons or has appeared in the action (in most cases by filing an Answer.) No such "waiting period" applies to defendants. The right to discovery (seek more information) is "cut-off" 30 days before trial. A motion concerning discovery must be heard by the Court at least 15 days before trial. If the trial date is continued, this does not mean that the "cut-off" dates concerning discovery are continued as well. See CCP § 2024. Unless permission is obtained from the Court, the discovery "cut-off" dates are calculated from the initial trial date. Limits on discovery CCP § 2017.010 states that the information sought must be (1) "not privileged", (2) "relevant to the subject matter of the action", and (3) either admissible or "reasonably calculated to lead to the discovery of admissible evidence." There are many categories of information that are protected by statute or by the constitutional right of privacy from discovery. It is advisable to consult a treatise concerning the scope of discovery. IF YOU ARE REPRESENTING YOURSELF SEVERE CONSEQUENCES CAN RESULT FROM A FAILURE TO RESPOND TO DISCOVERY SERVED UPON YOU BY THE OTHER PARTIES TO THE LAWSUIT. If you are the plaintiff, your lawsuit can be dismissed. If you are a defendant, default can be entered. See CCP § 2023. To reiterate, it is advisable to consult with an attorney if you wish to sue or if you are sued. Motions to compel In general, two types of motions to compel are commonly filed. A motion to compel initial responses is addressed to one or more of the following types of discovery: form interrogatories, specially drafted interrogatories, inspection demands (not "requests for production"), and requests for admission. The governing statutes are CCP §§ 2030.290, 2031.300 and 2033.280 respectively. (CCP § 2030 applies to both form and specially drafted interrogatories.) This type of motion is filed when a party fails to serve a verified response. Verification means that the party providing the responses (answers) states under penalty of perjury of the laws of the State of California that the responses are true and correct. See CCP § 2015.5. The qualification "verified" is used because an unverified response is tantamount to no response at all. See Appleton v. Sup. Ct. (Cook) (1988) 206 Cal.App.3d 632, 636. Responses are served on the attorney for the opposing party or the opposing party if it is representing itself. They are not filed with the Court. See CCP §§ 2030.280, 2031.290 and 2033.270. Failure to respond timely results in a waiver of objections (subject to a few exceptions not dealt with here). See CCP § 2030.290, 2031.300 and 2033.280. A motion to compel initial responses to requests for admission is a special type of motion. Failure to respond before the hearing on the motion to compel means that all of the "matters" (facts) set forth in the requests for admission are deemed established as true. See CCP § 2033.280. For example, one party requests (asks) the other party to admit that he or she "ran the red light". No response is served. At the hearing, the Court will deem the fact as established--the party did "run the red light". Moreover, sanctions are mandatory for failure to respond to requests for admission. See Appleton v. Sup. Ct. (Cook) (1988) 206 Cal.App.3d 632, 636. The second type of motion is a motion to compel further responses. It is also addressed to one or more of the following types of discovery: form interrogatories, specially drafted interrogatories, inspection demands (not "requests for production"), and requests for admission. The governing statutes are CCP §§ 2030.300, 2031.310 and 2033.290 respectively. This type of motion is filed when the party that propounded the questions is not satisfied with the responses received. All of the statutes governing motions to compel further responses require a "meet and confer in good faith" effort to resolve the dispute prior to filing the motion. All of the statutes also require that the motion to compel be served within 45 days of service of the unsatisfactory responses (plus five days extension of time if responses served by mail). The only exception requires a written agreement between the parties involved extending time to file the motion. The deadline has been held to be "quasi-jurisdictional"--court cannot rule on motion filed beyond 45-day limit or without written agreement extending time. See Vidal Sassoon, Inc. v. Sup.Ct. (1983) 147 Cal.App. 3d 681; Sperber v. Robinson (1994) 26 Cal.App.4th 736, 745 and Sexton v. Sup. Ct. (Mullikin Med. Ctr.) (1997) 58 Cal.App.4th 1403, 1410. See also Standon Co., Inc. v. Sup.Ct. (Kim) (1990) 225 Cal.App.3d 898, 903. There are common mistakes regarding motions to compel initial and further responses to inspection demands. First, a motion to compel initial responses to inspection demands seeks a written response within the parameters of CCP § 2031.240. Producing documents in lieu of serving a written response is not compliance. See CCP § 2031.240 and 2031.260. Second, if in the written responses, the other party agreed to produce the documents for inspection and copying and then that party fails to produce, the remedy is a motion to compel compliance "as agreed upon". It is governed by CCP § 2031.320. It does not fall within the parameters of subsection (m). Third, any motion to compel further responses to inspection demands must show "good cause" for inspection. See CCP § 2031.310. This showing requires the moving party to set forth specific facts addressing the need to inspect the particular documents in dispute. It is insufficient to state that they need to be reviewed for context or similar reason. See Fireman’s Fund Ins. Co. v. Sup. Ct. (Paine Webber Real Estate Securities) (1991) 233 Cal.App.3d 1138. There are also various types of motions governing other means of discovery--depositions, physical examinations, mental examinations, expert witness designation, etc. These are more complicated motions and are not dealt with here. Ex ParteWhen is an "Ex Parte" application appropriate? An ex parte application for a court order, being an exception to the general requirement of serving a regularly noticed motion under CCP 1005, is permitted only in limited circumstances. In every case, the application must make the necessary "affirmative factual showing" to support the particular relief being obtained on an ex parte basis [See, CRC Rule 3.1202c]. Ex parte relief is most frequently sought in situations where there is a pressing need for immediate relief such that waiting to hear the matter on regularly noticed motion would cause prejudice or harm. However, to obtain ex parte relief on this basis, the party must make an affirmative showing to justify the departure from the standard noticed motion procedure set forth at CCP 1005. An example of this type of ex parte request is an application for an order shortening time to serve notice of an urgently needed motion. An application for an order shortening time must be supported by a declaration that makes an adequate showing of "good cause" for such relief. [CRC Rule 3.1300(b)]. Another example of this sort is an application for an ex parte writ of attachment, temporary restraining order or other provisional remedy needed on an urgent basis. Whenever provisional remedies are sought, the application must show full compliance with all requirements of the applicable statute or other law authorizing such provisional relief on an ex parte basis. Of course, ex parte relief may be sought in many other circumstances, and only the most common situations have been enumerated here. Other examples of when ex parte relief may be appropriate include (but are not limited to) certain preliminary matters in which no adverse party is affected by the relief (e.g., applications to appoint a guardian ad litem or for service by publication), and where applicable law specifically permits the relief to be obtained on an ex parte basis (e.g., CRC Rule 3.1320(h) [request for dismissal for failure to amend after demurrer sustained]). How to obtain a hearing date and file papers Parties making ex parte applications shall obtain a date and time for the hearing of the application from the Clerk (Civil Calendar Division). The court requests that the party seeking an ex parte order submit the application and all supporting papers and fees to the Clerk (in Room 401 at main courthouse) for filing not later than 9:00 on the date of the hearing. (See, Fresno County Superior Court, Local Rule 2.7). CRC Rule 3.1200-3.1207 notice and other procedural requirements Parties seeking ex parte relief must comply with all statutes, rules and case law applicable to the specific relief being sought. For example, if a provisional remedy such as a temporary restraining order, writ of attachment, etc., is sought, the party must show full compliance with the particular statutes and other laws applicable to such provisional remedy. In addition, Rule 3.1200 to 3.1207 of the California Rules of Court sets forth a number of mandatory rules relating to all ex parte applications. Applications for ex parte orders failing to comply with Rule 3.1200 to 3.1207 will be rejected. Here are a few of the essential requirements of Rule 3.1200 to 3.1207 which parties often fail to comply with:

Order shortening time When a party applies to the court for an ex parte order to shorten the time for filing and service of notice of motion (See, CCP 1005), the request must be adequately supported by a declaration showing "good cause" to justify the relief. (CRC Rule 3.1300(b)). Failure to show "good cause" is one of the most frequent grounds for denial of such ex parte applications. Summary Judgment MotionsWhen should I serve a motion for summary judgment/adjudication? Motions for summary judgment/adjudication may be served at any time after 60 days have elapsed since the general appearance of the party against whom the motion is directed. (CCP § 437c(a).) Also, the motion must be served at least 75 days before the hearing date, increased by 5 days if service is by mail if the address is within California, 10 days if the address is outside California but within the United States, and 20 days if the address is outside the United States. (Ibid.) The court does not have jurisdiction to hear motions that are not served in a timely manner. When should I serve and file opposition? Any opposition must be served and filed at least 14 days before the hearing date, unless the court for good cause orders otherwise. (CCP § 437c(b)(2). When should I serve and file the reply? The reply must be served and filed at least 5 days before the hearing date, unless the court for good cause orders otherwise. (CCP § 437c(b)(4).) Can I obtain an order shortening time for service on a motion for summary judgment/adjudication? No. The court does not have the authority to shorten the time for notice of a summary judgment motion. (McMahon v. Superior Court (2003) 106 Cal.App.4th 112, 118.) Can I file a joinder to another party's motion for summary judgment/adjudication? No. A joinder to summary judgment motion that does not contain its own notice of motion and separate statement of undisputed facts does not constitute a valid summary judgment motion, and the court cannot grant summary judgment based upon such a joinder. (Village Nurseries, L.P. v. Greenbaum (2002) 101 Cal.App.4th 26, 47.) What constitutes a valid separate statement? The separate statement must separately identify each cause of action, claim, issue of duty, or affirmative defense, and each supporting material fact claimed to be without dispute with respect to the cause of action, claim, issue of duty, or affirmative defense. (CRC 3.1350.) The statement must be in a two-column format, with the undisputed material facts in numerical sequence in the first column and the evidence that establishes those undisputed facts in the second column. (Ibid.) Citation to the evidence in support of each material fact must include reference to the exhibit, title, page, and line numbers. (Ibid.) What constitutes a valid opposing separate statement? The opposing separate statement must set out verbatim on the left side of the page the facts claimed by the moving party to be undisputed. (CRC 3.1350(f).) Below the asserted undisputed facts, the statement must set forth the evidence said to establish that fact, complete with the moving party’s references to exhibits. (Ibid.) On the right side of the page, directly opposite the recitation of the moving party’s statement of material facts and supporting evidence, the response must unequivocally state whether that fact is "disputed" or "undisputed". (Ibid.) If the opposing party contends there is a dispute, the party must state on the right side of the page, directly opposite the fact in dispute, the nature of the dispute and describe the evidence that supports the position that the fact is controverted. (Ibid.) That evidence must be supported by citation to exhibit, title, page, and line numbers in the evidence submitted. (Ibid.) May I obtain summary adjudication when the notice of motion specifies only a request for summary judgment? No. The notice of motion must specifically request that the moving party seeks summary adjudication in the alternative to summary judgment in order for the court to grant summary adjudication of individual claims, causes of action, or issues. (Homestead Savings v. Superior Court (Dividend Development Corp.) (1986) 179 Cal.App.3d 494, 498.) Otherwise, if there is a single triable issue as to any material fact, the court must deny the entire motion for summary judgment. (Ibid.) How long can my points and authorities brief be? The points and authorities in support of or in opposition to a motion for summary judgment/adjudication must be no more than 20 pages long, unless the moving party obtains leave of court. (CRC 3.1113(d).) The 20-page limit does not include exhibits, declarations, attachments, the table of contents, the table of authorities, or the proof of service. (Ibid.) The moving party may apply to the court ex parte to file a longer memorandum. (CRC 3.1113(e).) However, the party must file the application at least 24 hours before the brief is due, it must give the other parties written notice, and the application must state reasons for the additional pages. (Ibid.) Can an attorney file a declaration in support of or in opposition to a motion for summary judgment/adjudication? Normally, an attorney’s declaration is only sufficient if the facts stated are matters of which the attorney would be presumed to have personal knowledge, in other words, matters occurring during the course of the lawsuit. Otherwise, the declaration is generally inadmissible for lack of personal knowledge. (Maltby v. Shook (1955) 131 Cal.App.2d 349, 351-352.) May I submit new evidence in my reply? Generally speaking, no. New evidence may accompany the reply only in "the exceptional case." (Plenger v. Alza Corp. (1992) 11 Cal.App.4th 349, 362, fn. 8.) If the moving party submits new evidence with the reply, the opposing party is entitled to notice and an opportunity to respond to the new material. (Ibid.) ______________

|

||||||||||||||

|

Morris & Stone, LLP | 17852 E. 17th St., Suite 201, Tustin, CA 92780

Phone: 714-954-0700 | Fax: 714-242-2058 | Email: info@TopLawFirm.com Representing all of Southern California, including the cities of Los Angeles, Beverly Hills, Century City, Santa Monica, Long Beach, Ventura, Santa Barbara, Costa Mesa, Irvine, Anaheim, Fullerton, Santa Ana, Tustin, Newport Beach, Mission Viejo, San Clemente, Riverside, San Bernardino and San Diego, in Orange County Superior Court and all other Southern California State and Federal Courts.

|

|||||||||||||||

Some of these questions may seem surprising, but it is to be expected that someone who has never had any involvement with the court may have no clue how things work.

Of course, it should go without saying that none of

this can be taken as legal advice, nor should you

base any decision on anything I have said. I like

to be able to offer my thoughts on a matter in the

hope that they may help guide the potential client

toward a solution, but for actual legal advice I

would need to be retained in order to take the time

to review your situation and any supporting

documentation in detail.

Some of these questions may seem surprising, but it is to be expected that someone who has never had any involvement with the court may have no clue how things work.

Of course, it should go without saying that none of

this can be taken as legal advice, nor should you

base any decision on anything I have said. I like

to be able to offer my thoughts on a matter in the

hope that they may help guide the potential client

toward a solution, but for actual legal advice I

would need to be retained in order to take the time

to review your situation and any supporting

documentation in detail. Big, big mistake. I will immediately bring a motion to dispose of the action. Once filed, any dismissal will be viewed as a response to my motion, meaning that my client has prevailed on the merits. Even if I allow the case to go to trial, assuming there is no defense to the money owed, you will prevail only on the breach of contract action against the corporation. My individual client, on the other hand, will prevail on the breach of contract cause of action, and he and the

corporation will both prevail on the fraud cause of action. To prove fraud, you must show that the defendants had no intention to perform. Failing to pay because of a downturn in the market does not evidence an intent to defraud, only an inability to pay.

Big, big mistake. I will immediately bring a motion to dispose of the action. Once filed, any dismissal will be viewed as a response to my motion, meaning that my client has prevailed on the merits. Even if I allow the case to go to trial, assuming there is no defense to the money owed, you will prevail only on the breach of contract action against the corporation. My individual client, on the other hand, will prevail on the breach of contract cause of action, and he and the

corporation will both prevail on the fraud cause of action. To prove fraud, you must show that the defendants had no intention to perform. Failing to pay because of a downturn in the market does not evidence an intent to defraud, only an inability to pay.